|

Українська Народна Республіка Українська Народна Республіка |

|

|---|

|

Українська Народна Республіка Українська Народна Республіка |

|

|---|

Welcome to the page of Ukraine the way it looks like in the world of Ill Bethisad. In this alternate timeline, the Ukrainian People's Republic was not crushed by the Russian armies. Instead, it managed to survive, but to achieve that it had to sacrifice Galicia. Thus, while in Russia the bolsheviks were defeated by the White Armies, resulting in the SNOR regime, Ukraine quickly developed into a model democracy. However, this does not mean that life for the Ukrainians was easy. From 1937 onwards, it found itself once again within the Russian sphere of influence, and was the scene of, respectively, a military coup d'etat, the bloody Second Great War, German occupation, and subsequently one of the most harsh and cruel regimes ever met within the snorist bloc of nations. It would last until 1989 before democracy was restored.

Ukraine is one of the largest countries in Europe. It has a strategic position in Eastern Europe, bordering the Black Sea, the Romanian Federation and the Crimea in the South, the Republic of the Two Crowns in the West, Belarus in the North, and Russia in the North and East. The border with Russia runs through the Sea of Azov. The Ukrainian landscape consists mostly of fertile plains, or steppes, and plateaus, crossed by rivers such as the Dnipro, Siwerśkyj Doneć, Dnister and the Piwdennyj Buh as they flow south into the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The country has almost no mountains.

Ukraine has a mostly temperate continental climate, though a more mediterranean climate is found near the Crimean coast. Precipitation is disproportionately distributed; it is highest in the west and north and lesser in the east and southeast. Winters vary from cool along the Black Sea to cold farther inland. Summers are warm across the greater part of the country, but generally hot in the south.

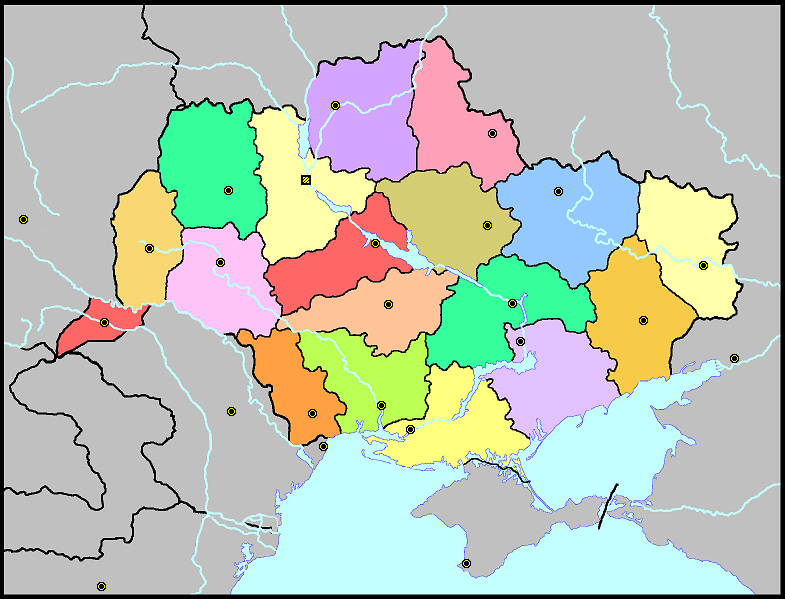

Ukraine is divided into 18 provinces (oblasts) plus the capital Kiev that has the same status as a province. Below is a map, followed by a table listing the provinces in alphabetical order, their names (short form and long form) written both in Cyrillic and Latin script. The short name of a province is always identical to the name of the city that is its administrative center.

NOTE: If you want to find out more about the countries surrounding Ukraine, you can click on their names.

| Long name | Short name, Administrative center | Area mi² (km²) | Population (2004) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Вінницька Область Winnyćka Obłaść | Вінниця Winnycia | 12,104 (26,513) | 2,109,121 |

| Донецька Область Donećka Obłaść | Донецьк Donećk | 12,106 (26,517) | 5,760,878 |

| Єлисаветградська Область Jełysawetgradśka Obłaść | Єлисаветград Jełysawethrad | 11,225 (24,588) | 1,348,332 |

| Житомирська Область Żytomyrśka Obłaść | Житомир Żytomyr | 13,619 (29,832) | 1,653,465 |

| Запорізька Область Zaporiźka Obłaść | Запоріжжя Zaporiżżia | 12,409 (27,180) | 2,295,713 |

| Іванівська Область Iwaniwśka Obłaść | Іванівка Iwaniwka | 8,160 (17,874) | 786,594 |

| Катеринославська Область Katerynosławśka Obłaść | Катеринослав Katerynosław | 14,597 (31,974) | 4,245,405 |

| Київська міська рада Kyiwśka miśka rada | Київ (city) Kyiw | 383 (839) | 3,107,479 |

| Київська Область Kyiwśka Obłaść | Київ (province) Kyiw | 12,843 (28,131) | 2,175,194 |

| Луганська Область Łuhanśka Obłaść | Луганськ Łuhanśk | 12,182 (26,684) | 3,029,952 |

| Миколаïвська Область Mykołaiwśka Obłaść | Миколаïв Mykołaiw | 11,230 (24,598) | 1,505,044 |

| Полтавська Область Połtawśka Obłaść | Полтава Połtawa | 13,125 (28,748) | 1,939,809 |

| Сумська Область Sumśka Obłaść | Суми Sumy | 10,881 (23,834) | 1,546,698 |

| Харківська Область Charkiwśka Obłaść | Харків Charkiw | 14,342 (31,415) | 3,467,912 |

| Херсонська Область Chersonśka Obłaść | Херсон Cherson | 12,994 (28,461) | 1,398,395 |

| Хмельницька Область Chmelnyćka Obłaść | Хмельницький Chmelnyćkyj | 9,425 (20,645) | 1,702,622 |

| Черкаська Область Czerkaśka Obłaść | Черкаси Czerkasy | 9,146 (20,034) | 1,669,533 |

| Чернівцька Область Czernihiwśka Obłaść | Чернівці Czerniwci | 3,360 (7,359) | 1,098,152 |

| Чернігівська Область Czernihiwśka Obłaść | Чернігів Czernihiw | 14,548 (31,865) | 1,481,859 |

| Ukrainian People's Republic | |

|---|---|

| 1917 - 1918 | Mychajło Hruszewśkyj |

| Ukrainian State | |

| 1918 | Pawło Skoropadśkyj |

| Ukrainian People's Republic | |

| 1918 - 1919 | Wołodymyr Wynnyczenko |

| 1919 - 1923 | Symon Petliura |

| 1923 - 1937 | Wołodymyr Wynnyczenko |

| Ukrainian State | |

| 1937 - 1944 | Bohdan Czajkowśkyj |

| German occupation | |

| 1944 - 1945 | Stepan Bandera |

| 1945 | Jarosław Stećko |

| Malorussia | |

| 1947 - 1950 | Josif Riadkowśkyj |

| 1950 - 1961 | Stanisław Czop |

| 1961 - 1973 | Serhij Bubko |

| 1973 - 1982 | Ostap Kyryłenko |

| 1982 - 1985 | Łeś Kondratiuk |

| 1985 - 1989 | Ihor Bezrucznyj |

| 1989 | Taras Krupnyk |

| Ukrainian People's Republic | |

| 1989 - 1994 | Jarosław Stus |

| 1994 - 1999 | Bohdan Rylśkyj |

| 1999 - date | Borys Hryńko |

There are few significant differences in Ukraine's history *here* and *there* before the 20th century. Until the Great War I Ukraine was part of Russia. In the period between the two Russian revolutions (the first brought Kerensky's provisional government to power, the second the Bolsheviks), Ukraine declared independence, but quickly became the scene of a violent war between the Bolsheviks, the White Armies, Ukrainian nationalists, and the Germans.

A Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR), fully independent from Russia, was proclaimed on 22 January 1918 by the Centralna Rada ("Central Rada"), a huge body led by the famous historian Mychajło Hruszewśkyj, which acted as its parliament. However, as a direct result of the Brest-Litovsk treaty (March 1918), this government was overthrown with German help. On 29 April 1918 the UNR was dissolved. Instead, Ukraine became an independent state (Ukrainśka Derżawa - Ukrainian State) under combined German-Venedic protectorate with a kossack hetman, Pawło Skoropadśkyj, as its titular head. This government however enjoyed little internal support and was eventually overthrown by the Ukrainian nationalists, who then for the second time proclaimed the Ukrainian People's Republic in November 1918. Supreme authority in this new UNR was exercised by a collective body, the Direktorija ("Directorate"), first led by Wołodymyr Wynnyczenko and then, after February 1919, by Symon Petliura.

Initially, the UNR did quite a good job expelling the Russians from its territory. But soon enough, the UNR found itself on the losing side in a war on two fronts: one with Russia, the second with Veneda. The main reason for the conflict with the latter was the short-lived West Ukrainian People's Republic (ZUNR), the core of which was a predominantly ethnic Ukrainian territory previously known as Galicia that had declared its independence from Veneda on November 1, 1918, and unified with the UNR in January 1919. Giving it up was pretty unacceptable for both sides: its capital, Lwiw (Czytać Leoniór in Wenedyk), was considered an icon of Venedic culture, while Galicia as a whole had been a major spiritual center of the entire Ukrainian nation during the 19th century. But the more the White Armies consolidated their power in Russia, advancing also onto Ukrainian territory, the more the Directorate came to understand that it could not afford a war with Veneda without itself being completely overrun by Russia. Much to the fury of the Galician Ukrainians, the Directorate signed a peace with Veneda in June 1919: the UNR withrew its claim on Galicia in exchange for military assistance against Russia and the promise that Galicia would enjoy an autonomous status within Venedic borders. This decision, albeit a hard one, changed to course of history: the UNR freed its hands and successfully expelled the remaining Bolsheviks and subsequently the White Armies from its territory.

Thus, the UNR managed to establish itself as an independent state instead of being crushed by Russia. However, the price was high: Galicia was lost to Veneda, Volhynia to the newly created state of Lithuania. Besides, Transnistria (including the city of Odesa) was lost to Moldova, which had proclaimed its independence from Russia in May 1918, and quickly thereafter used Ukraine's weakness to seize Transnistria from the Ukrainians.

During the first decade of its existence, the Ukrainian People's Republic flourished. On 7 March 1920, a constitution was adopted. The Centralna Rada was restored as the republic's parliament, while all executive power was in the hands of a five-headed presidential body, the Direktorija ("Directorate"), and a government. Head of the Directorate ("general director") remained Symon Petliura, but after the 1923 elections this function was taken over again by Wołodymyr Wynnyczenko. Wynnyczenko remained in office until 1937.

Ukraine was pretty much what one would call a model democracy. Political life was dominated by social-democrats and socialists, the country enjoyed its independence, and almost every party had both "socialism" and "Ukrainian" in its name, because that is what the time spirit was like. Most notable among the parties that formed the political scene were the following:

This period was characterised by a huge national revival and a relative stability. But despite all successes, the country grew more unstable in the 1930s. The socialist parties became the scene of internal strife, and governments succeeded each other at quick pace. The relationship with Russia was problematic from the beginning: Russia's new leadership was very frustrated about the deplorable state Russia was in after the war, and they were decided to do all that laid within its possibilities to restore the old empire.

Almost equally complicated were the relations with Ukraine's other neighbours, Veneda and Lithuania. Many Ukrainian politicians could never quite swallow the fact that they had lost Galicia to Veneda in return for a ceasefire and some military assistance; especially since the Galicians were far from happy within Veneda's borders themselves. Even worse was the situation in Volhynia, the poorest part of interwar Lithuania, where the Ukrainians were treated as second-rate citizens on their own territory. On the other hand, many in Veneda itself hoped for a restoration of the old (pre-partitions) Rzejpybiełka, which would not only mean reunification with Lithuania, but also include huge parts of central Ukraine. During the 1930s, there were regular talks between Russian and Venedic officials, and it has been proven that a partition of Ukraine between Russia and Veneda was on the agenda more than once.

In May 1937, a Russian-inspired coup d'état put an end to nearly two decades of social-democratic leadership in Ukraine. With the support of ethnic Russians, russified Ukrainians, kossacks, rich landowners and part of the business elite, as well as part of the military and the police, both the Directorate and the Central Rada were disbanded and dismantled. Russia officially never crossed any borders, but it is suspected that Russian agents played a significant part in the coup as well. In any case, power was taken over by rightist and generally pro-snorist forces. The new government was a mishmash of conservatives, liberals, Ukrainian nationalists, Russians, and Pan-Slavists.

Under its new rulers, the UNR was quickly abolished, and the Ukrainian State (Ukrainśka Derżawa) was established, with Cossack leader Bohdan Czajkowśkyj as its dictator, carrying the title "grand-hetman".

Although the regime applied certain means of terror from the beginning, this remained within the boundaries of what would have been considered acceptable in those days. Many politicians were temporarily arrested or otherwise incapacitated, a few were murdered, but it did not come to a massive slaughter. The new government even included a few defected members of the USDRP, the URDP and the UNP, after their parties had been dissolved. After 1938, however, when the new regime was firmly established and backed up by Russia, its policies gradually became more harsh and more openly pro-Russian. The Ukrainian intelligentsia were repressed, tens of thousands of people were locked up in labour camps, and all kinds of opposition were dealt with by the State Security. Russian became the second official language of the country.

In 1939, Ukraine joined the ranks of Russia, Germany, Hungary, Greece and Belarus in the "Großartige Allianz". In September of that year, it participated in the Russian attack on Lithuania and was allowed to occupy Volhynia. In 1940, Ukraine attacked and incorporated Moldova and the Crimea, both with Russian support. However, to the disappointment of the Ukrainian nationalists who participated in the Czajkowśkyj government, Ukraine did not get two other (ethnically Ukrainian) territories it had hoped for: Galicia remained under German occupation, and the Bukovyna was annexed by Hungary. After this, their enthousiasm for the regime faded and it almost collapsed. Leftist forces were already preparing to take over power like they had done in 1918 after the fall of the Skoropadśkyj regime. With difficulties Czajkowśkyj managed to maintain his power, but Ukraine became an unreliable ally for the Allianz.

When an armed conflict in the Balkans between Serbs and Croats escalated into a German-Russian war, in 1943, Ukraine sided with Russia, but was quickly overwhelmed by the German-Hungarian forces. By the end of 1944, all Ukraine - as well as Belarus, Lithuania, the Baltic states and most of European Russia - was under solid German-Hungarian occupation. A group of radical Ukrainian nationalists established a pro-German government in Ukraine, led by Stepan Bandera as president and Jarosław Stećko as prime minister. They tried to convince the Germans into the creation of an all-Ukrainian puppet state, which would encompass both Ukraine proper, Galicia and Volhynia, but were never taken seriously by the German leader Adolf von Hessler, who prefered to go for the complete economic exploitation of the country.

In the years 1943-1946 the Second Great War was essentially a war between three parties: the Allied Powers, which after 1945 also included the Scandinavian Realm; what had remained of the Allianz (mostly Germany, Hungary, Greece, Ethiopia and China); and the Snorist Coalition (Russia with what had remained of its allies). But in 1946 Russia concluded a separate peace with the Allies, and this proved too much for the Allianz: Germany's progress into Russian territory was finally halted, and from that moment on the Allianz was pushed back quickly onto its own territory. In the second half of 1947, Russia and Ukraine had recovered all their territory.

|

| Flag of Little Russia under SLOB rule |

Russia followed a very particular strategy in all the countries it had "liberated", including Ukraine: it provided them with snorists governments and turned them into obedient puppet states. Because most of the Czajkowśkyj regime had been wiped out, and because Czajkowśkyj had turned out an unreliable ally anyway, Russia's leader Iosif Vissarionov decided not to restore him. Instead, he formed a government consisting solely of representatives of the SLOB (Слов’янське Братство, "Slavic Brotherhood"), a small pan-Slavist SNOR satellite that had participed in the Czajkowśkyj government and had never played a role of any significance before that. Leader of country became Josif Riadkovśkyj, who just like his predecessor styled himself "grand-hetman", despite the fact that he was not even a Cossack at all.

The SLOB became the embodiment of Russian hegemony over Ukraine, which had become less than a puppet state now. Even the name of the country changed: Ukraine was renamed Malorussia (Малороссия, "Little Russia"). Russian was proclaimed its one and only official language, and Ukrainian was now officially one of its dialects. Due to this change, the SLOB itself became the SLAB now. The Ukrainians were, of course, peeved at this development, suffering a hard time under severe repression.

|

This new state was to include also Galicia and Volhynia, although in 1947 the war was still raving in those lands. It was intended to become part of a chain of satellite states, which also included Estonia, Latvia, Skuodia, a Great-Belorussia, a strongly decimated Lithuania, a strongly diminished Veneda, Slevania, Hungary, Oltenia, Moldova, Muntenia, and the Crimea, as well as several countries further East. Things would turn out differently, since the Allies persisted in the restoration of the Republic of the Two Crowns; as a result, Galicia and Volhynia ended up with the RTC again, and Ukraine was restored in its prewar borders. Interestingly, Ukraine was also forced return two countries it had seized previously, Moldova (including Transnistria and Odesa) and the Crimea. It is not precisely known why. Presumably, Vissarionov hoped to slavicise Moldova, among other things by giving it a huge Slavic minority. In the case of the Crimea it has been suggested that Vissarionov never completely trusted the Ukrainians, and wanted to have them surrounded beforehand in case they would ever turn against him.

Also not precisely known is why Russia didn't fully incorporate Ukraine and Belarus, establishing them as semi-independent states instead. Probably, propaganda played a role here, not only directed at the Allies, but mainly directed at the Ukrainians and Belarussians in the RTC. Vissarionov still hoped to acquire their territories one day. It must, however, be said that Malo- and Belorussia's independence were mostly fake, and that they enjoyed even less liberties than countries like Latvia or Hungary. In 1949, Vissarionov established an international organisation called Union of Slavic States (SSG), besides Russia consisting of Malorussia, Belorussia, Skuodia, Moldova and the Crimea. It was intended to grow into a new state, which would pretty much include the territories Russia had lost in 1918. Later, this idea was abandoned by his successors. The SSG continued to exist as a cultural body, but was completely overshadowed by its economic and military counterparts, the CMAEC and the Riga Pact (founded in 1955 and 1957 respectively).

Snorist repression reached its peak under Riadkovśkyj's successor, Stanisław Czop (1950-1961). Czop was an ethnic Ukrainian, who in spite of that hated anything Ukrainian and pursued a course of severe russification of his country. He had made his carreer in the secret police under Czajkowśkyj and was known for his blind obedience towards his Russian masters. Czop was a genuine sadist, and under his leadership, an estimated million of people were killed, while hundreds of thousands of others were deported to Siberia. Almost all prewar politicians - not only those belonging to leftist parties, but also the nationalists and officials of the Czajkowśkyj regime - were either killed or forced to leave the country. He wiped out almost the entire Ukrainian intelligentsia, closed down schools and universities, cultural institutions, and persecuted the Ukrainian-Orthodox Church. The use of the Ukrainian language, even under private conditions let alone in public, was severely punished. Entire villages that according to Czop had collaborated with the Germans were burnt down and their populations murdered. Representatives of national minorities other than the Russians (Veneds, mostly), were either killed or forcefully "repatriated". Czop effectively turned Ukraine into one big jail, in which torture, hangings and even crucifictions were common business. It is said that he personally supervised or even performed hundreds or thousands of executions.

After Vissarionov's death in 1958, opposition against Czop rose, but he was more feared than anything, and Vissarionov's successor Andrei Vlasov tolerated him. However, after Vlasov had been deposed in 1961, one of the first actions of Russia's new leader Yevgeni Lipov was liberating Malorussia of its hated leader. Czop was replaced as leader of the SLAB with another ethnic Ukrainian, Serhij Bubko (1961-1973).

Bubko effectively put an end to the terror of his predecessor. He released thousands of prisoners, loosened censorship somewhat, and even allowed for a moderate reukrainisation of the country. He endeavoured partnership with Russia on a more equal base, but on the other hand barely succeeded in achieving that purpose. Mass-immigration from Russia continued, and on the international scene Malorussia remained Russia's faithful partner.

Bubko died in 1973. After that, Malorussia's political history was mostly a reflection of that of Russia. He was succeeded by Ostap Kyryłenko, under whose leadership corruption rose to proportions similar to those in Russia. In 1982, Russia's mad leader Porfiri Bogolyubov replaced him with a personal acquaintance, the priest Łeś Kondratiuk. In 1985, shortly before in Russia Mikhail Gorbachenko came to power, Kondratiuk was replaced with the moderate reformist Ihor Bezrucznyj.

When in Russia the power of the SNOR began to crumble, Bezrucznyj could not prevent the same thing from happening in Malorussia. At last a huge revolution broke out - known to historians as the Yellow Revolution. In a last effort to keep the SLAB in charge, Bezrucznyj stepped back in October 1989 and had himself replaced by a very progressive, democraticaly oriented member of the party, Taras Krupnyk, but it was no good and after a few weeks the people finally overthrew the government. Shortly thereafter, the SLAB was banned.

|

| Flag of Ukraine, 1989- |

After the first free elections, the first official decision of the new parliament was renaming the state "Ukrainian People's Republic" once again. Subsequently, all institutions of the old UNR were restored: among others, the Centralna Rada and the Directorate. The first freely-elected general-director (= president) of Ukraine was Jarosław Stus, a former dissident who had spent more than thirty years of his life in prison. After his term came to an end in 1994, he was succeeded by the social-democrats Bohdan Rylśkyj (1994-1999) and Borys Hryńko (1999-date). Although the SLAB/SLOB itself has been banned, former officials of the party can still be found on many levels of society. Several of its successor parties are growing in popularity, and in the 2004 elections, Hryńko beat his post-slobist opponent Wiktor Januszczenko only with a small difference.

Nowadays, Ukraine maintains close relations with the Republic of the Two Crowns and it an aspirant member of the Baltic League. The country's economic situation remains very problematic, though.

Ukrainian culture is deeply rooted in ancient traditions, mostly that of the Medieval state of Kievan Rus'. The three major influences are: Byzantine culture, Russian culture, and Venedic culture. However, Ukraine has been part of the Russian Empire for centuries, and this has left its mark. Especially during the second half of the 19th century, as well as during the snorist era, russification has been severe. Due to the fact that Ukrainian intellectuals and native Ukrainian culture have been persecuted for such a long time, Ukrainian culture has a very rural and folkloristic character.

Ukraine still has a large Russian minority, especially in the East of the country. In the same regions, many ethnic Ukrainians would rather identify with the Russian nation than with their own. For a long time, it has been official policy that the Ukrainians are part of the Russian nation, and that Ukrainian is nothing but a rural dialect of Russian. Many Ukrainians still suffer under this conviction, called by sociologists the "Malorussian complex".

On the other hand, not all those who actually dó consider the Ukrainians a separate nation agree about its range. The common opinion among linguists is that Ukrainian and Ruthenian (the language spoken in Galicia) are one and the same language, despite the fact that the Ruthenian language has been more heavily influenced by Wenedyk and is written in Latin script, whereas Ukrainian is closer to Russian and written in Cyrillics; some even believe that the language of the Rusyns in Karpatia, Slevania and the RTC is also a Ukrainian dialect. The truth is, however, that West and East Ukrainians have pretty much drifted apart into two separate nations, the Ruthenes and the Ukrainians (or even three, if one also counts the Rusyns).